Droop Control for Frequency Converters (Inverters) – A Plain-Language Guide

1. What it is

Droop control imitates the natural speed-droop characteristic of a traditional synchronous generator. It lets several motors or inverters work in parallel without any data cable between them, automatically sharing the load.

2. The basic idea (one-sentence version)

“Whoever works harder runs a tiny bit slower; whoever works less runs a tiny bit faster.”

3. How it works in plain words

When a motor suddenly sees more load, its output frequency drops a little.

The other motors feel that micro-slow-down and pick up the extra kilowatts.

When the load decreases, the process reverses.

No master controller is required; each unit decides for itself.

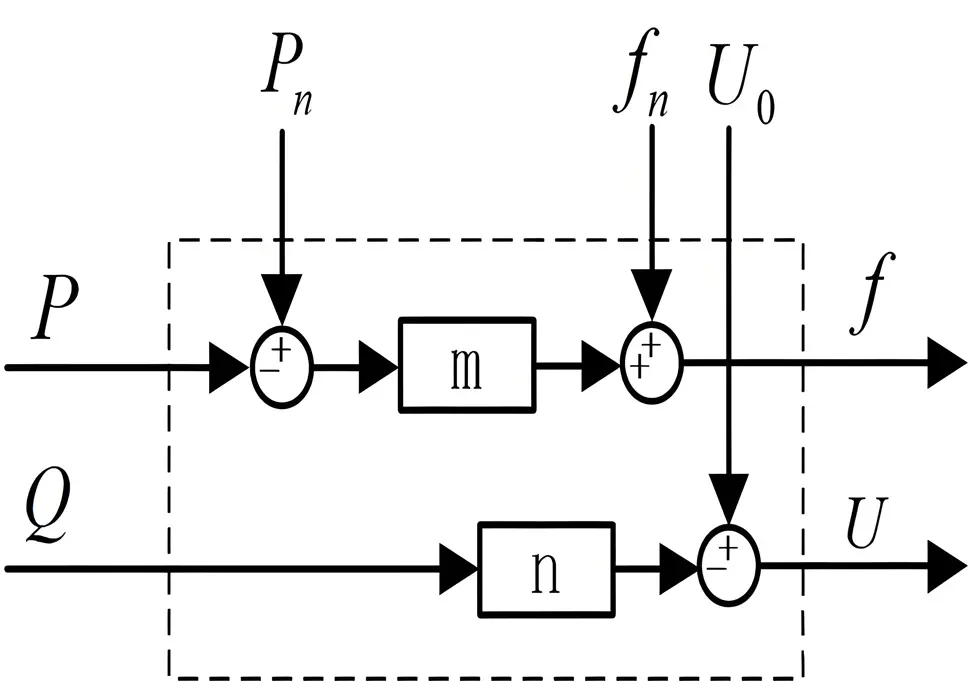

4. Key equation (frequency droop)

f = f₀ – kₚ · P

f: actual output frequency

f₀: no-load frequency set-point

kₚ: frequency-droop coefficient (Hz per kW)

P: active power the unit is delivering

5. Where it is used

Multi-motor conveyor belts – keeps every motor equally loaded

Gantry crane long-travel drives – keeps both sides synchronized so the crane does not skew

Micro-grids or battery inverters – keeps many small sources in parallel without communication

6. Pros and cons

Advantages

No communication wires needed; simple and rugged

Natural redundancy—if one unit trips, the others absorb its share

Behaves like a real generator, so power-system operators understand it

Drawbacks

Steady-state error: frequency and voltage move away from the nominal value

Load-sharing accuracy depends on cable impedance and calibration

Slower dynamic response; may need supplementary control for fast transients

7. One-line takeaway

Droop control turns a group of frequency converters into self-balancing teammates: they automatically share the burden, running a hair slower when they shoulder more and a hair faster when they lighten up.