IGBT Technology in Inverters: A Comprehensive Guide to Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistors

1. Introduction to IGBT Technology

1.1 What is an IGBT?

An Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistor (IGBT) is a high-performance power semiconductor device that combines the best features of two widely used electronic components: the MOSFET (Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor) and the BJT (Bipolar Junction Transistor). This hybrid technology creates a versatile switching device capable of handling high voltages and large currents with exceptional efficiency.

Key Definition:

IGBT is a voltage-controlled power semiconductor device designed for high-power applications, serving as a fast electronic switch that can be precisely controlled to turn on and off thousands of times per second.

1.2 The Importance of IGBT in Modern Electronics

IGBT technology has revolutionized power electronics by enabling:

- Efficient Power Conversion: Significantly reducing energy losses in electrical systems

- Precise Control: Allowing accurate regulation of power flow and motor speed

- Compact Design: Enabling smaller, lighter power electronic equipment

- Cost-Effectiveness: Providing superior performance at competitive pricing

In industrial automation, IGBTs are often referred to as the “CPU of power electronics” due to their central role in controlling and converting electrical energy.

1.3 IGBT vs Traditional Power Devices

|

Device Type

|

Control Method

|

Key Advantages

|

Key Disadvantages

|

Typical Applications

|

|

IGBT

|

Voltage-controlled

|

High input impedance, low conduction loss, fast switching

|

Higher cost than BJT

|

Inverters, motor drives, power supplies

|

|

MOSFET

|

Voltage-controlled

|

Extremely fast switching, simple gate drive

|

High conduction loss at high voltages

|

Low-power applications, consumer electronics

|

|

BJT

|

Current-controlled

|

Low conduction loss, mature technology

|

Complex drive circuit, slow switching

|

Legacy systems, low-frequency applications

|

|

GTO

|

Current-controlled

|

High power handling capability

|

Complex drive requirements, slow switching

|

High-voltage DC transmission

|

2. IGBT Structure and Working Principle

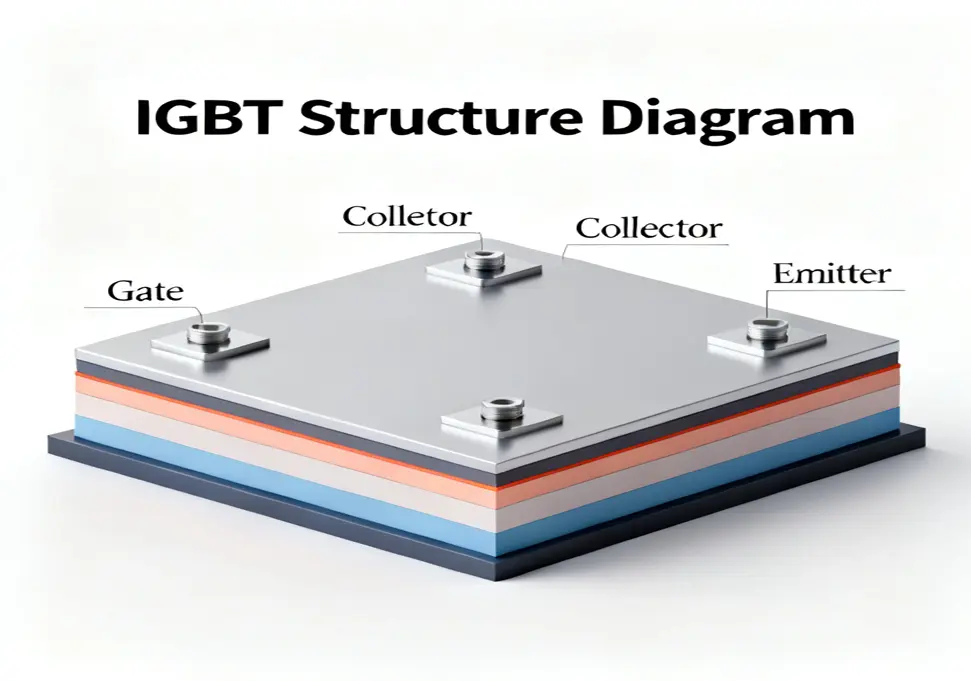

2.1 Basic IGBT Structure

An IGBT consists of multiple layers of semiconductor materials arranged in a specific configuration to achieve its unique performance characteristics. The device features three main terminals: Gate (G), Collector (C), and Emitter (E).

**

Semiconductor Layer Structure (from top to bottom):

- Emitter Layer (N+): Source of electrons for current conduction

- Base Layer (P): Controls the flow of electrons through the device

- Drift Layer (N-): Supports high voltage and provides current path

- Buffer Layer (N+): Improves switching speed and reduces losses

- Collector Layer (P+): Collects electrons and completes the circuit

2.2 IGBT Working Principle

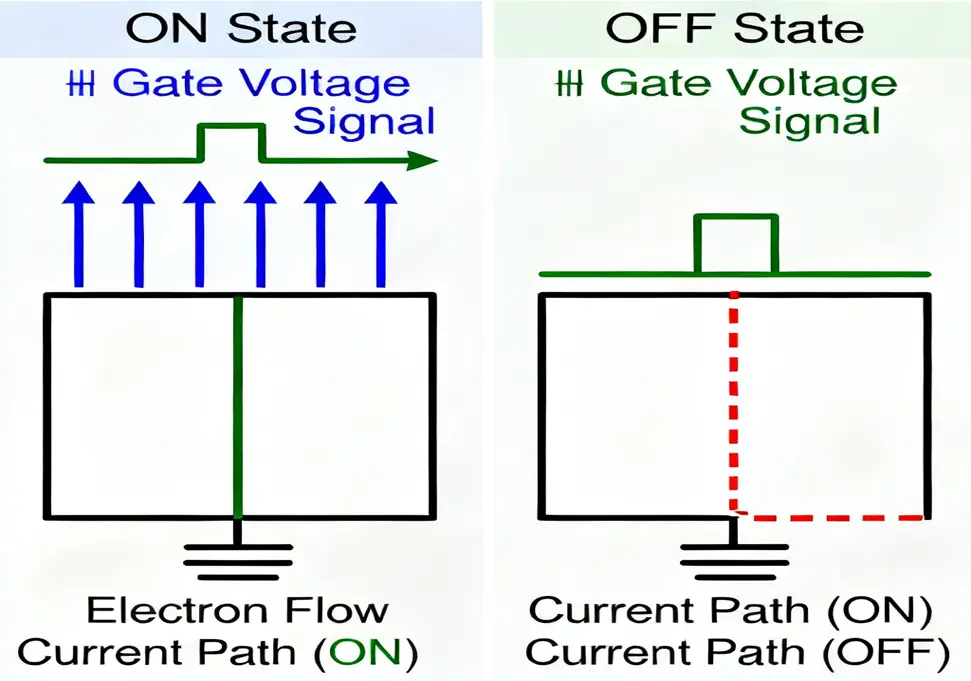

The operation of an IGBT can be best understood by examining its two primary operating states: ON (conducting) and OFF (non-conducting).

**

ON State Operation:

- A positive voltage is applied to the Gate terminal (typically +15V)

- This creates an electric field that forms a conductive channel in the P-base layer

- Electrons flow from the N+ emitter through the channel into the N- drift region

- The high concentration of electrons in the drift region causes the P+ collector to inject holes

- The combination of electrons and holes creates a low-resistance path between Collector and Emitter

- Large current flows with minimal voltage drop (typically 1-3V)

OFF State Operation:

- The Gate voltage is reduced to zero or negative voltage (typically 0V or -15V)

- The electric field collapses, and the conductive channel disappears

- Electron flow from the emitter is completely cut off

- Remaining charge carriers in the drift region are swept out

- The device returns to a high-resistance state

- Only a small leakage current flows between Collector and Emitter

2.3 Switching Characteristics

IGBTs exhibit several important switching characteristics that influence their performance:

Turn-on Characteristics:

- Delay Time: Time from Gate voltage application to 10% of rated current

- Rise Time: Time for current to increase from 10% to 90% of rated value

- On-state Voltage: Minimum voltage drop during conduction

Turn-off Characteristics:

- Storage Time: Time from Gate voltage removal to 90% current reduction

- Fall Time: Time for current to decrease from 90% to 10% of rated value

- Tail Current: Slow current decay due to minority carrier recombination

Typical Switching Parameters:

- Switching Frequency: 1kHz to 100kHz for power applications

- Turn-on Time: 0.1 to 1μs

- Turn-off Time: 0.5 to 5μs

- On-state Voltage: 1 to 3V

3. Role of IGBT in Power Inverters

3.1 Inverter Fundamentals

An inverter is a power electronic device that converts direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC). This conversion is essential for powering AC motors from DC sources such as batteries, solar panels, or rectified mains power.

Basic Inverter Components:

- Rectifier: Converts AC input to DC

- Filter: Smooths the DC voltage

- Inverter Bridge: Converts DC back to AC using power switches

- Control Circuit: Regulates the output frequency and voltage

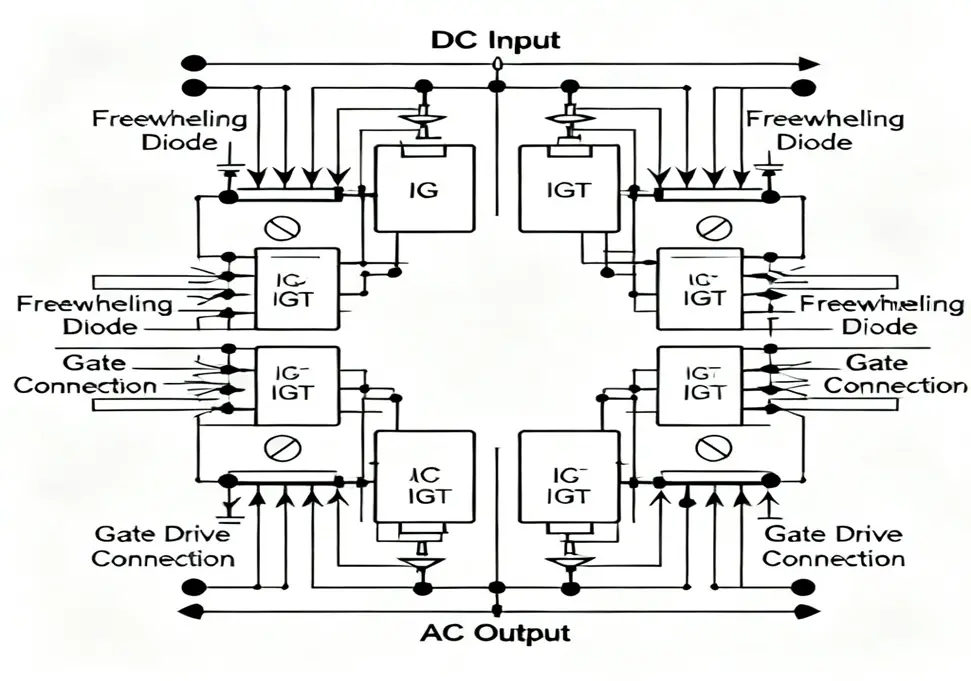

3.2 IGBT as the Inverter’s Power Switch

In modern inverters, IGBTs serve as the primary switching devices in the inverter bridge. Their ability to handle high voltages and currents while maintaining fast switching speeds makes them ideal for this critical application.

**

Three-Phase Inverter Configuration:

- Typically uses 6 IGBTs arranged in a bridge configuration

- Each phase leg consists of two IGBTs (upper and lower)

- Controlled by PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) signals

- Outputs three-phase AC power for motor control

3.3 PWM Control Technique

Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) is the key technique used to control IGBTs in inverters:

PWM Operating Principle:

- The control circuit generates high-frequency pulses (2kHz to 20kHz)

- The width of these pulses is varied to control the average output voltage

- By precisely timing the switching of each IGBT, a sinusoidal AC waveform is synthesized

- The frequency of the output waveform is determined by the repetition rate of the PWM pattern

Benefits of PWM Control:

- Precise Speed Control: Enables exact regulation of motor speed

- Smooth Operation: Reduces torque ripple and mechanical stress

- Energy Efficiency: Minimizes power losses in the motor

- Flexible Control: Supports various control strategies (V/F, vector control)

3.4 Inverter Operation Modes

IGBTs in inverters operate in several different modes depending on application requirements:

V/F Control Mode:

- Voltage-to-Frequency ratio maintained constant

- Simple control algorithm

- Suitable for fan and pump applications

- IGBTs switch at fixed frequency

Vector Control Mode:

- Motor current decomposed into flux and torque components

- More complex control requiring feedback

- Provides precise torque control

- IGBTs switch at variable frequency based on motor requirements

Regenerative Braking Mode:

- IGBTs operate in reverse to feed energy back to DC bus

- Requires additional control logic

- Used for applications requiring frequent braking

- Energy can be dissipated or returned to grid

4. Key Characteristics and Performance Parameters

4.1 Electrical Characteristics

IGBTs exhibit several important electrical characteristics that define their performance:

Voltage Ratings:

- Collector-Emitter Voltage (Vce): 600V to 6500V

- Gate-Emitter Voltage (Vge): ±20V (absolute maximum)

- Operating Gate Voltage: +15V (on), 0V or -15V (off)

Current Ratings:

- Continuous Collector Current (Ic): From a few amps to several thousand amps

- Pulsed Collector Current (Icp): 1.5 to 2 times continuous rating

- Collector Current Density: Up to several hundred A/cm²

4.2 Performance Advantages

IGBTs offer several performance advantages over traditional power devices:

1. Voltage Control with Low Drive Power

- Voltage-controlled device requiring minimal drive current

- Gate drive power typically 1/10 of that required for BJT

- Simple drive circuits with low component count

2. Low Conduction Loss

- Bipolar conduction mechanism provides low on-state voltage drop

- Conducts large currents with minimal power dissipation

- Better thermal performance than MOSFET at high voltages

3. Fast Switching Speed

- Combines fast switching of MOSFET with high current capability of BJT

- Reduced switching losses compared to BJT and GTO

- Suitable for high-frequency power conversion

4. High Voltage and Current Handling

- Capable of handling voltages up to 6500V and currents up to several kA

- Suitable for medium to high power applications

- Rugged design with good overload capability

5. Positive Temperature Coefficient

- On-state resistance increases with temperature

- Prevents thermal runaway and allows parallel operation

- Improves reliability and system safety

4.3 Thermal Characteristics

Thermal management is critical for IGBT performance and reliability:

Temperature Ratings:

- Maximum Junction Temperature (Tjmax): 125°C to 175°C

- Operating Junction Temperature: Should be kept below 125°C for long life

- Thermal Resistance (Rthjc): 0.1 to 1°C/W

Heat Dissipation Mechanisms:

- Conduction Losses: Dominant at low frequencies

- Switching Losses: Dominant at high frequencies

- Gate Losses: Generally negligible compared to other losses

Thermal Management Solutions:

- Heat Sinks: Passive cooling using aluminum fins

- Forced Air Cooling: Fans for higher power applications

- Liquid Cooling: Water or oil cooling for high-power modules

- Thermal Interface Materials: Improve heat transfer between IGBT and heat sink

5. IGBT Applications Across Industries

5.1 Industrial Motor Drives

IGBTs are widely used in various types of motor drives:

AC Drives:

- Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs): Most common application for IGBTs

- Servo Drives: Precise position and speed control

- Soft Starters: Controlled motor starting to reduce inrush current

- Traction Drives: Locomotives, electric vehicles, and elevators

DC Drives:

- Chopper Drives: DC motor speed control

- Regenerative Drives: Energy recovery systems

- Battery Chargers: Industrial battery charging systems

5.2 Power Supply Applications

IGBTs play important roles in various power supply systems:

Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPS):

- Online UPS systems for critical loads

- Standby UPS for computer systems

- High-power UPS for data centers

Switched-Mode Power Supplies (SMPS):

- High-power industrial power supplies

- Medical power supplies

- Telecommunication power systems

Power Factor Correction (PFC):

- Active PFC circuits in power supplies

- Three-phase PFC systems

- Grid-connected PFC systems

5.3 Renewable Energy Systems

IGBTs are essential components in renewable energy generation:

Solar Power Systems:

- Grid-tie inverters for photovoltaic systems

- Solar battery storage systems

- Solar water pumping systems

Wind Power Systems:

- Wind turbine converters

- Doubly-fed induction generator (DFIG) systems

- Full converter wind turbines

Energy Storage Systems:

- Battery energy storage systems (BESS)

- Flywheel energy storage

- Supercapacitor energy storage

5.4 Transportation Applications

IGBTs are transforming transportation systems worldwide:

Electric Vehicles (EVs):

- EV traction inverters

- On-board battery chargers

- DC-DC converters for auxiliary systems

Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs):

- Power control units (PCUs)

- Motor drive systems

- Energy management systems

Rail Transportation:

- Electric locomotive traction systems

- Light rail and metro systems

- High-speed train power systems

5.5 Consumer Electronics

Even in consumer products, IGBTs find important applications:

Home Appliances:

- Induction cooktops and ranges

- Microwave ovens

- Air conditioners and heat pumps

- Washing machines and dryers

Audio Equipment:

- High-power audio amplifiers

- Professional sound systems

- Home theater systems

6. IGBT Protection and Thermal Management

6.1 Protection Circuitry

Implementing proper protection is critical for IGBT reliability:

Overcurrent Protection:

- Current Sensing: Shunt resistors, current transformers

- Comparator Circuits: Detect overcurrent conditions

- Shutdown Logic: Rapidly turn off IGBT during faults

- Soft Shutdown: Controlled turn-off to minimize voltage spikes

Overvoltage Protection:

- Voltage Clamping: TVS diodes, snubber circuits

- Zener Diodes: Protect gate circuit from overvoltage

- RC Snubbers: Suppress voltage transients

- Active Clamping: Dynamic voltage regulation

Overtemperature Protection:

- Thermistors: Temperature sensing elements

- Thermal Switches: Discrete temperature protection

- Integrated Temperature Sensors: Built-in temperature monitoring

- Thermal Shutdown: Automatic shutdown at safe temperature limits

Gate Drive Protection:

- Gate Resistors: Limit gate current and dv/dt

- Gate Zener Diodes: Protect gate oxide from overvoltage

- Isolation: Galvanic isolation between control and power circuits

- Dead-time Control: Prevent shoot-through in bridge circuits

6.2 Thermal Management Design

Effective thermal management is essential for reliable IGBT operation:

Heat Sink Design:

- Material Selection: Aluminum or copper for high thermal conductivity

- Fin Geometry: Optimized for maximum heat dissipation

- Surface Treatment: Anodization for corrosion resistance

- Mounting Pressure: Proper torque for good thermal contact

Cooling Methods:

- Natural Convection: Passive cooling for low-power applications

- Forced Air Cooling: Fans for medium-power applications

- Liquid Cooling: Water or oil cooling for high-power applications

- Two-Phase Cooling: Advanced cooling for very high-power systems

Thermal Interface Materials:

- Thermal Grease: Low-cost solution for moderate performance

- Thermal Pads: Easy-to-apply pre-formed pads

- Thermal Adhesives: For permanent bonding

- Phase Change Materials: Offer best thermal performance

6.3 Layout Considerations

Proper PCB layout is critical for IGBT system performance:

Power Layout:

- Short Current Paths: Minimize parasitic inductance

- Wide Copper Traces: Handle high currents without overheating

- Ground Plane: Provide low-impedance return path

- Isolation Barriers: Maintain safety isolation between high and low voltage

Gate Drive Layout:

- Short Gate Traces: Minimize gate drive delays

- Symmetrical Layout: Equal lengths for parallel devices

- Separate Power and Signal Grounds: Prevent ground loops

- Shielding: Protect gate signals from interference

7. Troubleshooting Common IGBT Issues

7.1 Common Failure Modes

IGBTs can fail in several different ways, each with distinct characteristics:

Short-Circuit Failure:

- Symptoms: Low resistance between Collector and Emitter, often catastrophic

- Causes: Overcurrent, voltage spikes, insufficient protection

- Detection: Low resistance measurement, overcurrent tripping

Open-Circuit Failure:

- Symptoms: No current flow between Collector and Emitter

- Causes: Bond wire failure, die cracking, overheating

- Detection: High resistance measurement, no output voltage

Gate Oxide Failure:

- Symptoms: Gate leakage, erratic switching behavior

- Causes: Overvoltage on Gate, ESD damage, manufacturing defects

- Detection: Abnormal gate current, switching irregularities

Thermal Runaway:

- Symptoms: Rapid temperature rise, device destruction

- Causes: Insufficient cooling, overcurrent, positive feedback

- Detection: Temperature monitoring, thermal shutdown activation

7.2 Root Cause Analysis

Understanding the root causes of IGBT failures is essential for prevention:

Electrical Stress Factors:

- Overvoltage: Voltage transients exceeding device ratings

- Overcurrent: Current exceeding safe operating limits

- dv/dt Stress: Excessive voltage slew rates

- di/dt Stress: Excessive current slew rates

- Gate Drive Issues: Incorrect gate voltage, insufficient drive current

Thermal Stress Factors:

- Overheating: Insufficient cooling, high ambient temperature

- Thermal Cycling: Temperature variations causing mechanical stress

- Hot Spots: Localized heating due to poor thermal management

- Thermal Resistance: High resistance path for heat flow

Mechanical Stress Factors:

- Vibration: Mechanical vibration causing bond wire fatigue

- Shock: Mechanical shock from handling or equipment operation

- Temperature Cycling: Thermal expansion/contraction cycles

- Humidity: Moisture ingress causing corrosion

7.3 Testing and Diagnosis Procedures

Proper testing is essential for identifying IGBT problems:

Visual Inspection:

- Check for physical damage to package

- Look for signs of overheating (discoloration, burning)

- Inspect solder joints and connections

- Check for corrosion or contamination

Electrical Testing:

- Diode Test: Check internal freewheeling diode

- Resistance Measurement: Check Collector-Emitter and Gate-Emitter resistance

- Capacitance Measurement: Check input and output capacitance

- Threshold Voltage Test: Verify proper gate voltage requirements

Functional Testing:

- Static Testing: Check basic switching functionality

- Dynamic Testing: Measure switching times and losses

- Thermal Testing: Monitor temperature rise under load

- Overload Testing: Verify protection circuit operation

7.4 Preventive Maintenance Practices

Regular maintenance can significantly extend IGBT life:

Periodic Inspection:

- Visual Inspection: Check for signs of damage or wear

- Connection Check: Verify tightness of electrical connections

- Cooling System Check: Clean heat sinks, check fans and filters

- Insulation Check: Test insulation resistance

Performance Testing:

- Output Voltage Test: Verify correct output waveform

- Current Measurement: Check for abnormal current levels

- Temperature Monitoring: Measure operating temperatures

- Efficiency Test: Verify system efficiency

Preventive Measures:

- Cleaning: Regular cleaning of cooling systems

- Torque Checking: Periodic checking of connection torque

- Replacement Schedule: Preventive replacement of critical components

- Environmental Control: Maintain proper operating environment

Summary

IGBT technology has revolutionized power electronics and become the backbone of modern inverter systems. Its unique combination of high input impedance, low conduction loss, and fast switching speed makes it ideal for a wide range of applications from industrial motor drives to renewable energy systems.

Key Takeaways:

- IGBT Fundamentals: Understanding the structure and working principle of IGBTs is essential for proper application and troubleshooting.

- Performance Characteristics: IGBTs offer superior performance compared to traditional power devices, with key advantages in efficiency, control, and reliability.

- Inverter Applications: IGBTs serve as the critical switching elements in inverter circuits, enabling precise control of AC motor speed and torque.

- Protection and Thermal Management: Proper protection circuitry, thermal management, and maintenance practices are essential for maximizing IGBT reliability and lifespan.

- Troubleshooting: Systematic diagnosis and root cause analysis are critical for resolving IGBT issues and preventing future failures.

By mastering the concepts and techniques presented in this guide, engineers and technicians can effectively design, implement, and maintain IGBT-based systems for optimal performance and reliability.